library(R6)Docstrings

Learning objectives:

- Understand what docstrings are and why they are important.

- Learn how to write effective docstrings.

Relevant reproducibility guidelines:

- STARS Reproducibility Recommendations: Comment sufficiently.

- NHS Levels of RAP (🥈): Code is well-documented including user guidance, explanation of code structure & methodology and docstrings for functions.

Docstrings: what and why

Docstrings (“documentation strings”) are used to describe what each object in your code does. They should be included everywhere: modules, functions, classes, methods, and tests.

Example:

def add_positive_numbers(a, b):

"""

Add two positive numbers.

Parameters

----------

a : float

First number to add (must be positive).

b : float

Second number to add (must be positive).

Returns

-------

float

The sum of a and b.

"""

if a < 0 or b < 0:

raise ValueError("Both numbers must be positive.")

return a + bDocstrings (“documentation strings”) are used to describe what each object in your code does. They should be added to functions and classes.

Example:

#' Add two positive numbers

#'

#' @param a First number to add (must be positive).

#' @param b Second number to add (must be positive).

#'

#' @return The sum of a and b.

#' @export

add_positive_numbers <- function(a, b) {

if (a < 0L || b < 0L) stop("Both numbers must be positive.", call. = FALSE)

a + b

}How do they differ from in-line comments?

Docstrings explain the overall purpose of a code object (like a function or class), while in-line comments clarify individual lines or sections of code when the logic isn’t obvious.

For example, we could add an in-line comment to the function above to explain the if statement:

# Check if both inputs are positive before adding

if a < 0 or b < 0:

raise ValueError("Both numbers must be positive.")

return a + b# Check that both inputs are positive before adding

if (a < 0L || b < 0L) stop("Both numbers must be positive.", call. = FALSE)

a + bWhy use docstrings?

Clarity and consistency: Docstrings make code easier to understand and provide a uniform way to document your work, which is especially valuable when collaborating.

Maintainability and reproducibility: They help future users (including yourself) see the purpose and usage of code, making ongoing maintenance and reuse simpler and less error-prone. (Hence, their inclusion in the NHS Levels of RAP silver criteria (🥈)!)

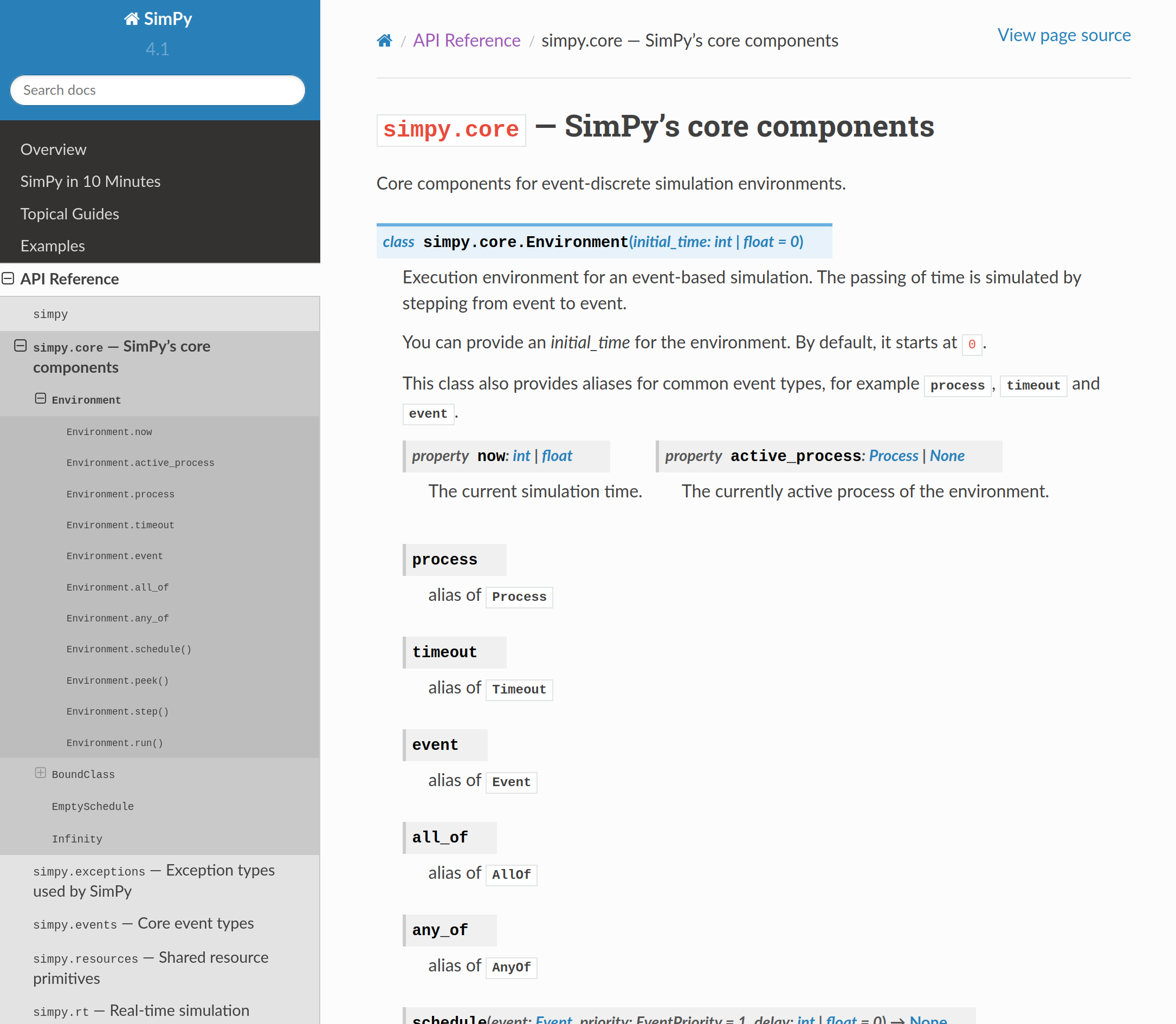

Documentation websites: If you create a package and build a documentation website (e.g. with a tool like

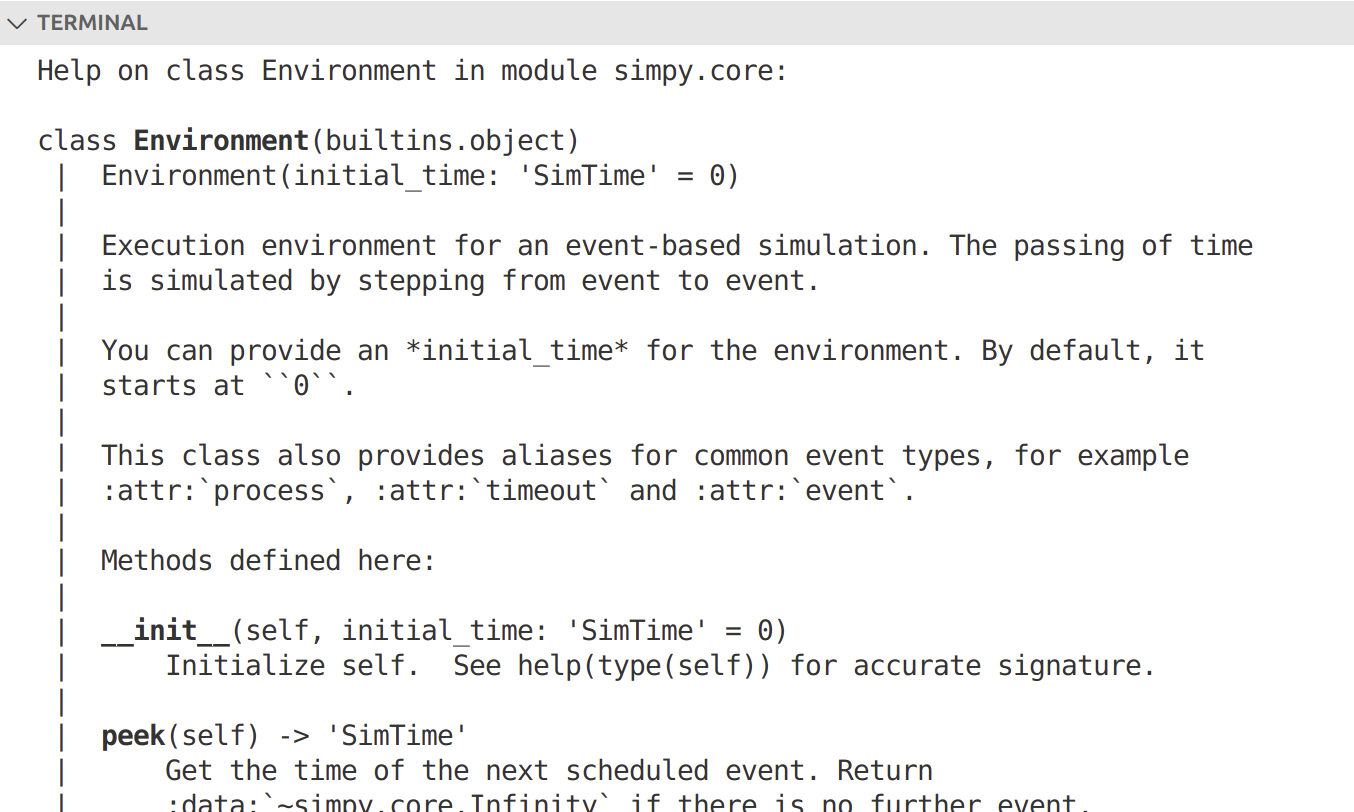

quartodoc), the docstrings are automatically used to generate reference guides and manuals. For example:Interactive help systems: Docstrings are picked up by interactive help tools like

help(function), which displays the docstring directly in the console or interface, to explain how the function or class works. For example…Open a python script, or open on terminal by calling:

pythonImport SimPy and load the documentation for the

Environment()class.library(simpy) help(simpy.core.Environment)This will display:

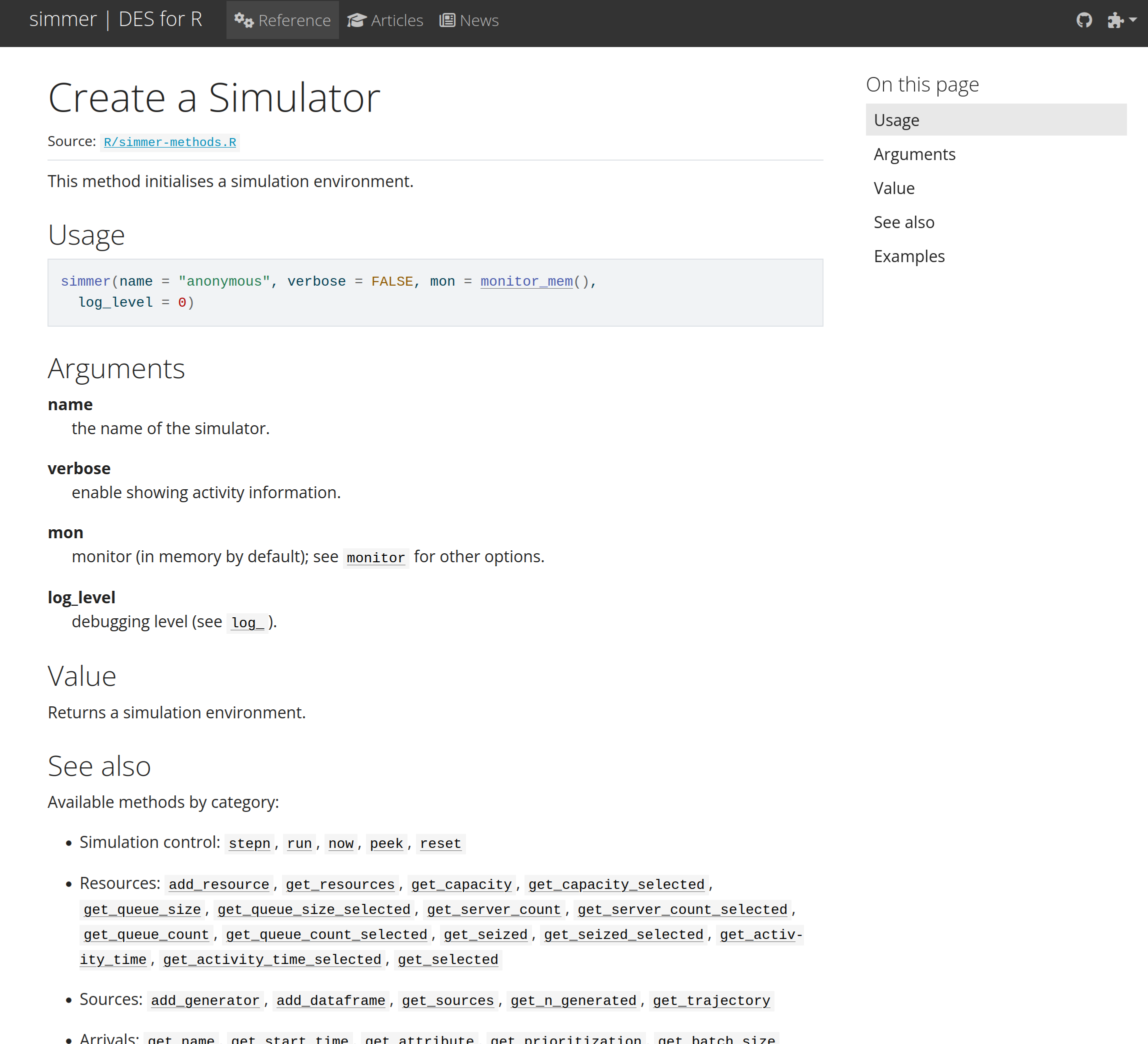

Documentation websites: If you create a package and build a documentation website (e.g. with a tool like

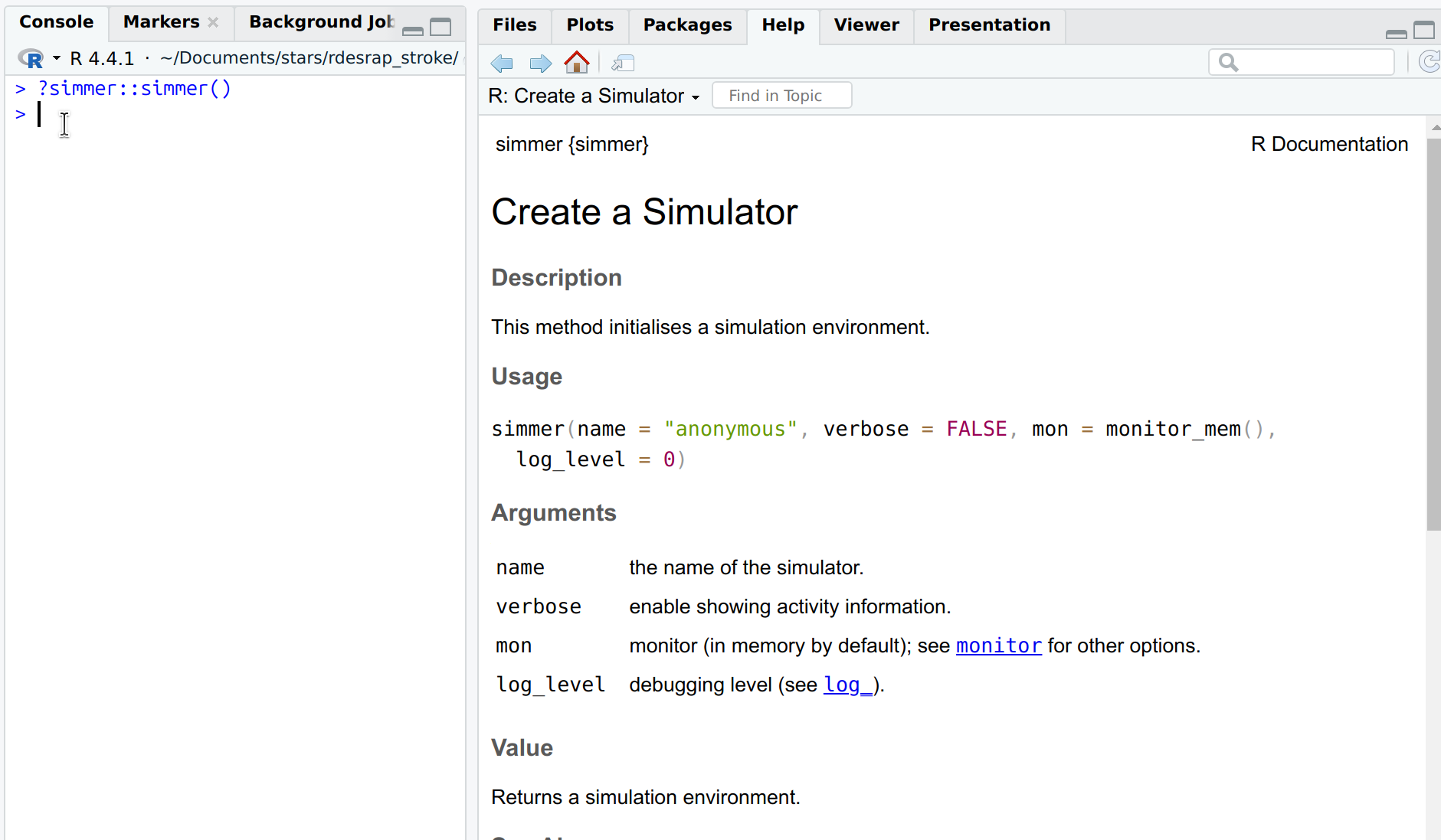

quartodocorpkgdown), the docstrings are automatically used to generate reference guides and manuals. For example:Help systems: When comments follow a docstring format, you can view them in help panels with

?function. For example:

How to write docstrings

There are a variety of style guides and standardized docstring formats available for Python, many of which are supported by automated documentation tools, linters, and code editors. Choosing a consistent style improves code readability and makes it easier for others to understand and use your code.

Two popular ones include:

- NumPy style docstrings - numpydoc.

- Google style docstrings - google style guide.

In our example models, we have used NumPy style. Below, we illustrate both approaches for comparison.

Function

NumPy style:

def estimate_wait_time(queue_length, avg_service_time):

"""

Estimate the total wait time for all customers in the queue.

Parameters

----------

queue_length : int or float

Number of customers currently in the queue.

avg_service_time : int or float

Average time taken to serve one customer.

Returns

-------

float

Estimated total wait time.

"""

return queue_length * avg_service_timeGoogle style:

def estimate_wait_time(queue_length, avg_service_time):

"""Estimate the total wait time for all customers in the queue.

Args:

queue_length (int or float): Number of customers currently in the

queue.

avg_service_time (int or float): Average time taken to serve one

customer.

Returns:

float: Estimated total wait time.

"""

return queue_length * avg_service_timeClass

NumPy style:

class Patient:

"""

Represents a patient in a healthcare facility.

Attributes

----------

patient_id : int or str

Unique identifier for the patient.

arrival_time : str or datetime-like

The time when the patient arrived.

status : str

Current status of the patient: one of "waiting", "admitted", or

"discharged".

"""

def __init__(self, patient_id, arrival_time):

"""

Initialise a new patient record.

Parameters

----------

patient_id : int or str

Unique identifier for the patient.

arrival_time : str or datetime-like

The time when the patient arrived.

"""

self.patient_id = patient_id

self.arrival_time = arrival_time

self.status = "waiting"

def admit(self):

"""Admit the patient."""

self.status = "admitted"

def discharge(self):

"""Discharge the patient."""

self.status = "discharged"Google style:

class Patient:

"""Represents a patient in a healthcare facility.

Attributes:

patient_id (int or str): Unique identifier for the patient.

arrival_time (str or datetime-like): The time when the patient arrived.

status (str): Current status of the patient, one of "waiting",

"admitted", or "discharged".

"""

def __init__(self, patient_id, arrival_time):

"""Initialise a new patient record.

Args:

patient_id (int or str): Unique identifier for the patient.

arrival_time (str or datetime-like): The time when the patient

arrived.

"""

self.patient_id = patient_id

self.arrival_time = arrival_time

self.status = "waiting"

def admit(self):

"""Admit the patient."""

self.status = "admitted"

def discharge(self):

"""Discharge the patient."""

self.status = "discharged"Test

Tests are a bit different. They usually just have a short, one‑line description without formal parameters or return sections, and are not based on any specific style guide.

Example:

def test_estimate_wait_time():

"""Test estimate_wait_time with sample input and expected output."""

assert estimate_wait_time(5, 2) == 10Module

A module is a .py file within a package containing package code, like functions or classes. Each .py file is considered a module, and modules can be used to group related code together.

Module docstrings - similar to tests - are usually brief, giving an overview of the file’s purpose and main contents, without necessarily following a strict style guide.

Example:

"""

hospital.py

A simple healthcare utility module.

Provides:

- A function to estimate patient wait times in a queue.

- A class to represent a patient and manage their admission status.

"""In R, docstrings are almost always written in roxygen2 style. This is because it is the standard for packages, and works seamlessly with R’s package tools.

The @export tag is included in each docstring to tell Roxygen to add the object to the package’s NAMESPACE file, making it available for users once they load the package with library(packagename).

Function

#' Estimate the total wait time for all customers in the queue.

#'

#' @param queue_length numeric Number of customers currently in the queue.

#' @param avg_service_time numeric Average time taken to serve one customer.

#'

#' @return numeric Estimated total wait time.

#' @export

estimate_wait_time <- function(queue_length, avg_service_time) {

queue_length * avg_service_time

}Class

#' Represents a patient in a healthcare facility.

#'

#' @docType class

#' @importFrom R6 R6Class

#' @export

Patient <- R6Class("Patient", list( # nolint: object_name_linter

#' @field patient_id integer or character. Unique identifier for the

#' patient.

patient_id = NULL,

#' @field arrival_time character or Date/POSIXt. The time when the patient

#' arrived.

arrival_time = NULL,

#' @field status character. Current status of the patient: one of

#' "waiting", "admitted", or "discharged".

status = NULL,

#' Initialise a new patient record.

#'

#' @param patient_id integer or character. Unique identifier for the

#' patient.

#' @param arrival_time character or Date/POSIXt. The time when the patient

#' arrived.

initialize = function(patient_id, arrival_time) {

self$patient_id <- patient_id

self$arrival_time <- arrival_time

self$status <- "waiting"

},

#' Admit the patient.

admit = function() {

self$status <- "admitted"

},

#' Discharge the patient.

discharge = function() {

self$status <- "discharged"

}

))Advice when writing docstrings

Write early! Add docstrings whilst you code or immediately afterward. If you leave them until later, you can easily forget important details.

Keep them concise.

Use AI wisely. Large language models can help draft docstrings, but review carefully - they may be too wordy, following a different format, or miss details.

Use linting tools. pydoclint (GitHub) is a great new tool for flagging formatting issues and missing parameters in docstrings.

Use linting tools. When you run devtools::check(), it will let you know about missing parameters in docstrings.

Explore the example models

Click to visit pydesrap_mms repository

Click to visit pydesrap_stroke repository

These repositories use NumPy style docstrings.

Click to visit rdesrap_mms repository

Click to visit rdesrap_stroke repository

These repositories use roxygen2 style docstrings throughout.

Test yourself

Try writing docstrings for functions from your own codebase.

Alternatively, practice by writing a docstring for the example function below.

def calculate_interarrival_time(arrival_rate):

return 1 / arrival_ratecalculate_interarrival_time <- function(arrival_rate) {

1 / arrival_rate

}Suggested solutions are provided, but try writing your own version first before checking them.

def calculate_interarrival_time(arrival_rate):

"""

Calculate the average inter-arrival time between patient arrivals.

Parameters

----------

arrival_rate : float

The average number of patient arrivals per time unit (e.g., per hour).

Returns

-------

float

The average time between two consecutive patient arrivals.

"""

return 1 / arrival_ratedef calculate_interarrival_time(arrival_rate):

"""Calculate the average inter-arrival time between patient arrivals.

Args:

arrival_rate (float): The average number of patient arrivals per time unit

(e.g., per hour).

Returns:

float: The average time between two consecutive patient arrivals.

"""

return 1 / arrival_rate#' Calculate the average inter-arrival time between patient arrivals.

#'

#' Given an arrival rate (patients per time unit), this function computes

#' the expected time between successive patient arrivals.

#'

#' @param arrival_rate Numeric. Average number of arrivals per time unit (e.g., per hour).

#'

#' @return Numeric. Average inter-arrival time between two consecutive patient arrivals.

#' @export

calculate_interarrival_time <- function(arrival_rate) {

1 / arrival_rate

}