Procedure overview#

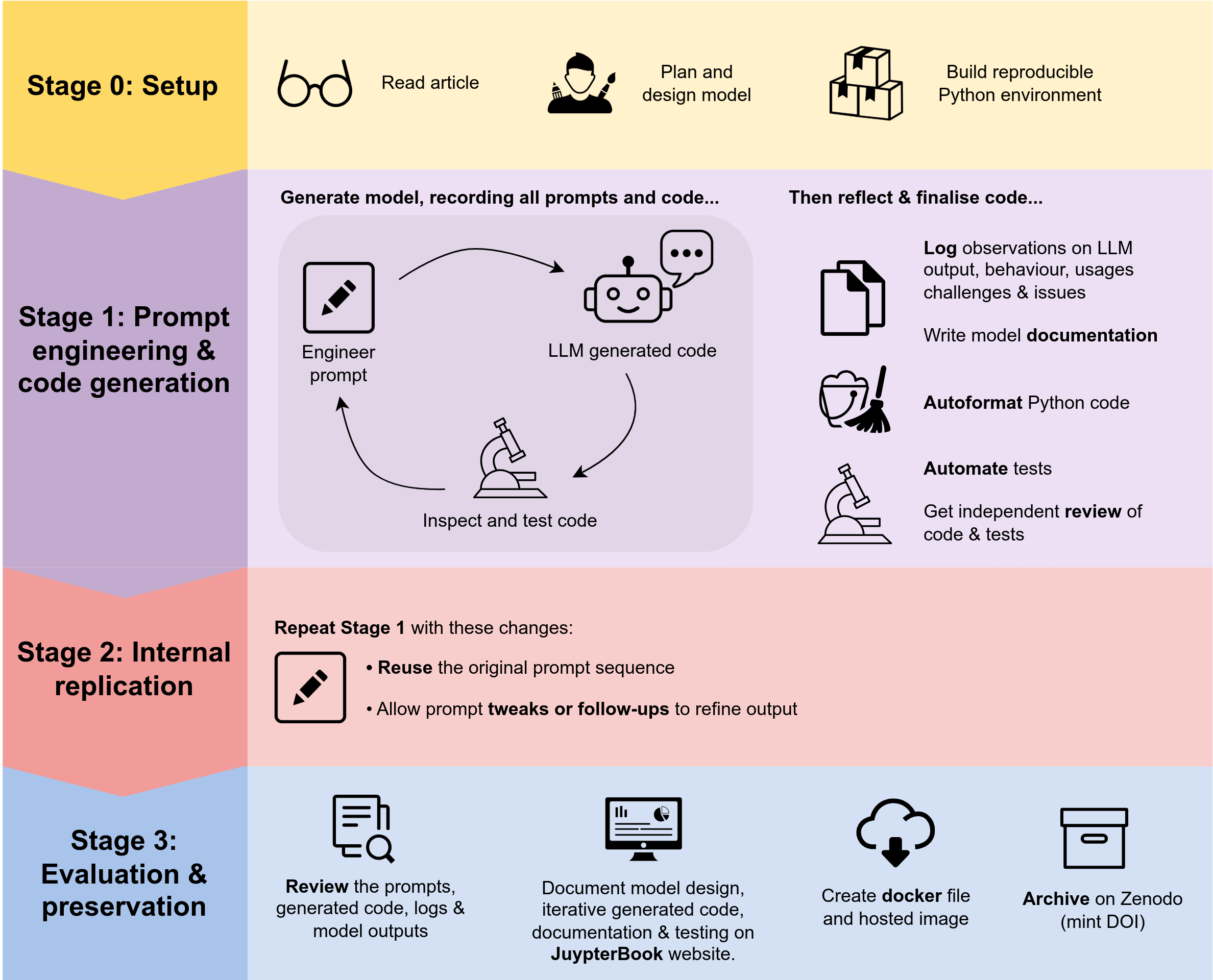

Our study followed four stages: a setup and model design (stage 0), an prompt engineering and code generation (stage 1), internal replication (stage 2), and evaluation and preservation (stage 3). Fig. 1 illustrates these stages and the activities conducted in each. We will shortly describe each stage of the study in detail, but here we provide a high level summary.

Fig. 1 General overview of activities in the DES model recreation experiment using generative AI.#

Stage 0: setup and model design#

In stage 0, we selected two healthcare DES case studies. Prior LLM coding studies had focused on very simple coding tasks comprising of 20-30 lines of code. We aimed to increase the complexity of the coding task for the LLM in our study. We selected DES models that consisted of multiple classes of patient (e.g. multiple arrival sources and differing sampling distributions for length of stay), and at least two activities (delays). From experience we estimated that our designs of such models would require between between 200 - 500 lines of Python code. We would still classify these as simple DES models. We read the academic papers and wrote down a design for a simulation model organised by the STRESS guideline format for reporting models [Monks et al., 2019]. Prior studies of reproducing models from journal articles have been challenging due to reporting ambiguities. We therefore document any simplifications or additional assumptions (e.g. undocumented parameters or logic or removal of a feature) that were made to enable us to design a functioning version of the model reported in the journal article. Once this was complete we designed a common Python 3.10 software environment (implemented as a conda virtual environment) that could be used in stages 1 to 3 for running the generated code.

Stage 1: prompt engineering and code generation#

In stage 1, we created a prompt database that contained a record of all prompts given to the LLM and for what purpose. We then proceeded to generate the design of the model reported in case study 1 and then, when complete, recreate case study 2. Where appropriate we reused or adapted prompts from case study 1 when recreating the model for case study 2. All case study prompts were stored in the database in sequence of use. After the models were complete we create a research compendium consisting of a STRESS report for the design, formatted model code (using the tool black), a script to run the model, documentation for the user interface, and an automated model test suite. A second modeller then reviewed the research compendium and identified any stage 1 modifications required before proceeding to stage 2.

Stage 2: internal replication#

In stage 2, a second modeller replicated stage 1. I.e. they attempted to recreate the models using the original sequence of prompts. Given the stochastic nature of creative LLM output (i.e. the same input prompt may not produce the same output), we allowed for re-engineering of prompts in the replication phase. This might be a direct modification to original prompt or an additional follow up prompt to modify output to the desired code. To be clear this means that we allow our models to be structurally different (use different Python data structures, and class/function designs). Stage 2 was added to the research compendium and independently checked in an identical manner to stage 1.

Stage 3: evaluation and preservation#

Evaluation#

In stage 3, we compared the artefacts generated and experience of working with the LLM to create the simpy models in stage 1 and 2. We defined a successful internal replication to be when stage 1 and 2 models produced the same results. As designed the models to use the same seeds and random number generators we aimed for identical results; however, we allowed a small tolerance of 5% inline with other replication studies [CITATION NEEDED].

The evaluate the use of the LLM for generating the models the modellers from stage 1 and 2 (TM and AH) initially synthesised their experience of prompting the LLM: identifying common successes/failings, general challenges, coding mistakes, and opportunities. These results were then reviewed and clarified by the two remaining members of the study team.

Model Preservation#

The final step in stage 3 was to preserve the models we had recreated so that they are available to others to inspect or use. We first created a Dockerfile that allowed us to build a container for the models and research compendium (an image of a complete reproducible software environment including operating system for others to run). We then deposited the research compendium in the open science archive Zenodo and obtained a DOI.

References#

Thomas Monks, Christine S. M. Currie, Bhakti Stephan Onggo, Stewart Robinson, Martin Kunc, and Simon J. E. Taylor. Strengthening the reporting of empirical simulation studies: introducing the stress guidelines. Journal of Simulation, 13(1):55–67, 2019. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/17477778.2018.1442155, doi:10.1080/17477778.2018.1442155.